Thursday, May 19, 2011

her conversation is utterly without interest...

A poem card - part of series featuring poems by Sinclair Beiles - published by Gerard Bellaart's Cold Turkey Press, France.

Sunday, May 15, 2011

’n Roerende chaos

Indien jy wil weet hoe jy in die laaste dekade verander het, hoef jy net ’n boek of ’n gedig te lees waarvan jy tien jaar gelede gehou het. Só het ek agtergekom vele literêre helde het intussen saam met my jeugdige romantiek en boheemse versugtinge gesneuwel.

Onder hierdie dooie ikone tel die meeste skrywers van die Beat-generasie wat die wêreld- letterkunde in die 1950s onherroeplik verander en die deure afgeskop het vir die kontra-kulturele revolusie van die 1960s..Read more here

Onder hierdie dooie ikone tel die meeste skrywers van die Beat-generasie wat die wêreld- letterkunde in die 1950s onherroeplik verander en die deure afgeskop het vir die kontra-kulturele revolusie van die 1960s..Read more here

Friday, May 13, 2011

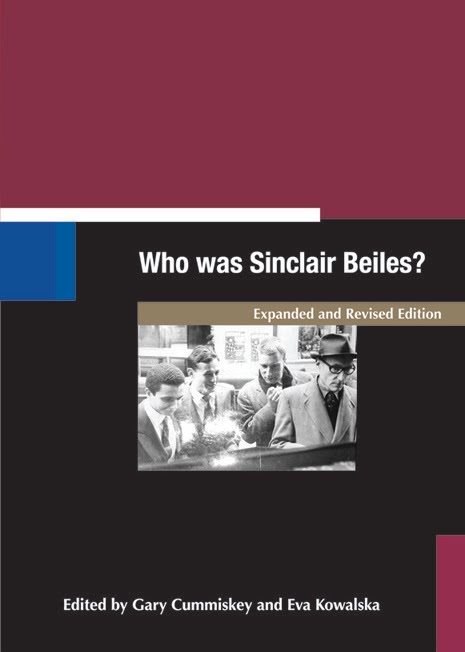

Collected works worth the effort: Fred de Vries interviews Gerard Bellaart

A Dutch publisher has been the self-appointed custodian of the works of SA poet Sinclair Beiles — who, he says, is a vastly underrated peer of the likes of Kerouac and Burroughs

A HAMLET in rural France, surrounded by sunflowers and vineyards, isn’t the most likely place to find a huge archive of the writing, letters, photos and pictures of SA’s legendary “beat poet”, Sinclair Beiles (1930-2000).

It’s almost surreal to see Dutch artist and publisher Gerard Bellaart carrying box after box of Beiles material from his studio so his visitor can work his way through piles of typed and handwritten pages, and marvel at the picture of Beiles and his American chum, Gregory Corso, in Athens in 1967. “I have some 1200 pages of unpublished material,” says Bellaart, who first encountered Beiles in 1967 in Greece, and kept up a correspondence with him until his death in 2000.

“It includes some stunning work, like The Idiot’s Voice and Inmates, which he wrote in a loony bin in London, where he met actress Sally Willis. She started a kind of therapy for him by giving him four subjects every day, which he would then turn into poetry. I also have the correspondence between them, which is extremely beautiful and touching.”

Beiles has often been dismissed as a marginal character in the beat history that was spearheaded by American writer Jack Kerouac in the mid-’50s. Beiles was responsible for the editing of William Burroughs’s masterpiece, Naked Lunch. And, with Burroughs, Corso and Brion Gysin he wrote Minutes to Go (1960), a tiny book that heralded the cut-up experiment in literature: writers doing a kind of remix of existing texts.

Beiles was born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1930, the only child of Jewish South African parents, who moved back to Johannesburg when their son was six years old. He studied at Wits University and left SA in the mid-’50s.

After time in New Zealand, Spain and Morocco he moved to Paris, which was then the centre of international bohemia. He stayed in the notoriously anarchic Beat Hotel on Rue Git-le-Coeur, a stone’s throw from the river Seine.

He became involved with the American beats. He also worked as an editor for Olympia Press, brainchild of maverick publisher Maurice Girodias, who not only gave us “forbidden” erotic pockets but also seminal literary work by the likes of Samuel Beckett, Vladimir Nabokov and Burroughs.

BEILES a beat writer? Way too facile, insists Bellaart. “I wouldn’t call him a beat poet. That’s such an empty phrase, it means nothing to me. Kerouac and those guys were no influence on Sinclair. I think he found them a bunch of country bumpkins.

“His cultural background was very European. They also didn’t have an eye for things visual. Sinclair had an exceptional eye for visual art.”

When the Paris scene fell apart in the early ’60s, most participants drifted south, doing the “karma circuit”, passing through Greece and eventually ending up in India, Kashmir and Tibet.

Beiles decided to stay in Greece, moving between Athens and the island of Hydra, where he befriended Canadian troubadour Leonard Cohen. “What you had in Greece was a wave of expatriates, writers, artists and aristocrats like Princess Zina Rachesvsky. All of them outsiders and drifters,” remembers Bellaart, who hitchhiked from Rotterdam to Athens after he fell in love with Greek music that a truck driver played when he gave him a lift in Finland.

He bumped into Beiles at a party in Athens. They immediately got along. “I visited his flat and still remember how I walked in and saw poems. Poems everywhere. One of them was called Notes from the Promised Land, which ended up in Ashes of Experience, for which he won the Ingrid Jonker Award in 1970.”

Beiles had a history of mental instability. Diagnosed with manic depression as a teenager, he was subjected to electroshock treatment, and spent many months in psychiatric wards in Athens, London, Paris and Johannesburg.

His illness made him unpredictable and occasionally volatile.

Publishers were reluctant to deal with the “mad South African”, who once, in a fit of anger, threw a suitcase full of poems at an important London literary star.

Bellaart, however, wasn’t afraid. In 1970 he started his own publishing company, Cold Turkey Press, specialising in maladjusted writers such as Charles Bukowski, Antonin Artaud and Ezra Pound. Beiles fitted the bill perfectly. Here was a poet who assaulted deadening reality through a descent into delirium and fantasy.

“I saw him as the Holy Fool in the Russian tradition, not loony, but very wise,” says Bellaart, who published limited editions of Beiles’s Sacred Fix and Deliria, both now highly collectable.

AFTER Beiles returned to SA in the late ’70s, he married fellow poet Marta Proctor. They moved into a house in Yeoville, Johannesburg, and Beiles became a genuine Yeoville character, whose star rapidly waned during that highly politicised pre-1994 era.

Few were interested in the surrealist poetry and plays of that sickly man who used to scurry down Rockey Street, bumming coffee off friends and acquaintances. Most people found him initially entertaining, but soon became fed up with his antics and fantastic stories.

“Eventually he became like an untouchable,” says Bellaart.

“So he started making photocopies of his poems, stapled them and published them in editions of 15 or something, and sold some to Unisa.”

Bellaart, who never saw Beiles after the mid-’70s, still refuses to see his friend in terms of mad and normal. “He was very lucid in his descriptions of insanity. Is someone like that mad or normal? Those extremes are not applicable to Sinclair.

“It’s very hard to grasp him. Like all those fantastic stories he used to tell. They all happened within his own reality.

“That was the source of his poetry. And most did have a source of truth in them.”

Largely due to his worsening bipolar condition, Beiles fell out with almost everyone. Bellaart was an exception. They had a brief quarrel about a prose poem called Aardvark, in which Beiles tackled the decadence of the Lost City. Beiles thought it was his ultimate tour de force and wanted Bellaart to publish it.

BELLAART, however, could not make head or tale of it. “He sent me at least five versions. Just when I read my way through the previous one, he sent me a new one. I tried to deconstruct it, all the different characters. But I just couldn’t.”

Towards the end of his life, in 1997, Beiles did finally receive some recognition when the French Cultural Institute organised a Beat Hotel exhibition in Carfax, which featured a reconstruction of the Beat Hotel facade and two rooms, complete with a replica of Gysin’s hypnotic Dream Machine. Beiles read poems and had his 15 minutes of fame.

THREE years later he died, dismissed as a footnote to the beat history. An unjust epitaph, says Bellaart, showing me some of the exquisite mid-period poems. “He was hugely cultured. He had an enormous curiosity and an incredible ability to absorb things.

“I see Sinclair as someone who was outside everything. He had no affiliation with any movement. He was the most original of that whole late-’50s Paris scene. But because of his unevenness and his chaotic personal life, he was also the easiest to marginalise, to neglect. And to treat with condescension.”

The archives of Burroughs, Ginsberg, Corso, Kerouac, Bukowski, all contemporaries of Beiles, have been bought for huge sums by American universities and collectors, who are proud of their writers and poets.

The Beiles files are stored somewhere in rural France, waiting to change ownership. “They belong in kind, caring South African hands,” says Bellaart.

(Published in The Weekender, 16 August, 2008)

A HAMLET in rural France, surrounded by sunflowers and vineyards, isn’t the most likely place to find a huge archive of the writing, letters, photos and pictures of SA’s legendary “beat poet”, Sinclair Beiles (1930-2000).

It’s almost surreal to see Dutch artist and publisher Gerard Bellaart carrying box after box of Beiles material from his studio so his visitor can work his way through piles of typed and handwritten pages, and marvel at the picture of Beiles and his American chum, Gregory Corso, in Athens in 1967. “I have some 1200 pages of unpublished material,” says Bellaart, who first encountered Beiles in 1967 in Greece, and kept up a correspondence with him until his death in 2000.

“It includes some stunning work, like The Idiot’s Voice and Inmates, which he wrote in a loony bin in London, where he met actress Sally Willis. She started a kind of therapy for him by giving him four subjects every day, which he would then turn into poetry. I also have the correspondence between them, which is extremely beautiful and touching.”

Beiles has often been dismissed as a marginal character in the beat history that was spearheaded by American writer Jack Kerouac in the mid-’50s. Beiles was responsible for the editing of William Burroughs’s masterpiece, Naked Lunch. And, with Burroughs, Corso and Brion Gysin he wrote Minutes to Go (1960), a tiny book that heralded the cut-up experiment in literature: writers doing a kind of remix of existing texts.

Beiles was born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1930, the only child of Jewish South African parents, who moved back to Johannesburg when their son was six years old. He studied at Wits University and left SA in the mid-’50s.

After time in New Zealand, Spain and Morocco he moved to Paris, which was then the centre of international bohemia. He stayed in the notoriously anarchic Beat Hotel on Rue Git-le-Coeur, a stone’s throw from the river Seine.

He became involved with the American beats. He also worked as an editor for Olympia Press, brainchild of maverick publisher Maurice Girodias, who not only gave us “forbidden” erotic pockets but also seminal literary work by the likes of Samuel Beckett, Vladimir Nabokov and Burroughs.

BEILES a beat writer? Way too facile, insists Bellaart. “I wouldn’t call him a beat poet. That’s such an empty phrase, it means nothing to me. Kerouac and those guys were no influence on Sinclair. I think he found them a bunch of country bumpkins.

“His cultural background was very European. They also didn’t have an eye for things visual. Sinclair had an exceptional eye for visual art.”

When the Paris scene fell apart in the early ’60s, most participants drifted south, doing the “karma circuit”, passing through Greece and eventually ending up in India, Kashmir and Tibet.

Beiles decided to stay in Greece, moving between Athens and the island of Hydra, where he befriended Canadian troubadour Leonard Cohen. “What you had in Greece was a wave of expatriates, writers, artists and aristocrats like Princess Zina Rachesvsky. All of them outsiders and drifters,” remembers Bellaart, who hitchhiked from Rotterdam to Athens after he fell in love with Greek music that a truck driver played when he gave him a lift in Finland.

He bumped into Beiles at a party in Athens. They immediately got along. “I visited his flat and still remember how I walked in and saw poems. Poems everywhere. One of them was called Notes from the Promised Land, which ended up in Ashes of Experience, for which he won the Ingrid Jonker Award in 1970.”

Beiles had a history of mental instability. Diagnosed with manic depression as a teenager, he was subjected to electroshock treatment, and spent many months in psychiatric wards in Athens, London, Paris and Johannesburg.

His illness made him unpredictable and occasionally volatile.

Publishers were reluctant to deal with the “mad South African”, who once, in a fit of anger, threw a suitcase full of poems at an important London literary star.

Bellaart, however, wasn’t afraid. In 1970 he started his own publishing company, Cold Turkey Press, specialising in maladjusted writers such as Charles Bukowski, Antonin Artaud and Ezra Pound. Beiles fitted the bill perfectly. Here was a poet who assaulted deadening reality through a descent into delirium and fantasy.

“I saw him as the Holy Fool in the Russian tradition, not loony, but very wise,” says Bellaart, who published limited editions of Beiles’s Sacred Fix and Deliria, both now highly collectable.

AFTER Beiles returned to SA in the late ’70s, he married fellow poet Marta Proctor. They moved into a house in Yeoville, Johannesburg, and Beiles became a genuine Yeoville character, whose star rapidly waned during that highly politicised pre-1994 era.

Few were interested in the surrealist poetry and plays of that sickly man who used to scurry down Rockey Street, bumming coffee off friends and acquaintances. Most people found him initially entertaining, but soon became fed up with his antics and fantastic stories.

“Eventually he became like an untouchable,” says Bellaart.

“So he started making photocopies of his poems, stapled them and published them in editions of 15 or something, and sold some to Unisa.”

Bellaart, who never saw Beiles after the mid-’70s, still refuses to see his friend in terms of mad and normal. “He was very lucid in his descriptions of insanity. Is someone like that mad or normal? Those extremes are not applicable to Sinclair.

“It’s very hard to grasp him. Like all those fantastic stories he used to tell. They all happened within his own reality.

“That was the source of his poetry. And most did have a source of truth in them.”

Largely due to his worsening bipolar condition, Beiles fell out with almost everyone. Bellaart was an exception. They had a brief quarrel about a prose poem called Aardvark, in which Beiles tackled the decadence of the Lost City. Beiles thought it was his ultimate tour de force and wanted Bellaart to publish it.

BELLAART, however, could not make head or tale of it. “He sent me at least five versions. Just when I read my way through the previous one, he sent me a new one. I tried to deconstruct it, all the different characters. But I just couldn’t.”

Towards the end of his life, in 1997, Beiles did finally receive some recognition when the French Cultural Institute organised a Beat Hotel exhibition in Carfax, which featured a reconstruction of the Beat Hotel facade and two rooms, complete with a replica of Gysin’s hypnotic Dream Machine. Beiles read poems and had his 15 minutes of fame.

THREE years later he died, dismissed as a footnote to the beat history. An unjust epitaph, says Bellaart, showing me some of the exquisite mid-period poems. “He was hugely cultured. He had an enormous curiosity and an incredible ability to absorb things.

“I see Sinclair as someone who was outside everything. He had no affiliation with any movement. He was the most original of that whole late-’50s Paris scene. But because of his unevenness and his chaotic personal life, he was also the easiest to marginalise, to neglect. And to treat with condescension.”

The archives of Burroughs, Ginsberg, Corso, Kerouac, Bukowski, all contemporaries of Beiles, have been bought for huge sums by American universities and collectors, who are proud of their writers and poets.

The Beiles files are stored somewhere in rural France, waiting to change ownership. “They belong in kind, caring South African hands,” says Bellaart.

(Published in The Weekender, 16 August, 2008)

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Offerings of Fire by Marta Proctor

Offerings of Fire by Sinclair Beiles's wife Marta Proctor, published in 1985 by Two Cities Johannesburg and Two Cities Paris. Sinclair wrote the introduction to this chapbook of 24 poems.

Tuesday, May 10, 2011

Whatever happens is meat for my poetry...

"I can't tell whether I'm cynical or optimistic - whether there is something out there organising a life of pleasure or pain for us. It's beyond my scope. Things happen to me. I record what happens. I don't care why. Whatever happens is meat for my poetry. My poetry and my personality are synonymous. I enjoy reading cosmological works but haven't been able to discern any pattern to my existence or any rhythmical relation between myself and others. I don't hunger after being part of a total harmony or tragedy or feel 'alienated' in any way." - Sinclair Beiles, letter to Gerard Bellart, editor of Cold Turkey Press, May 1969.

Labels:

Cold Turkey Press,

Gerard Bellaart,

Sinclair Beiles

Monday, May 2, 2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)